The artist searches for authenticity, even if it means he might not survive. Are lack, austerity, and pain mandatory to feed the true creative process?

by Cristina Slattery

See the NYC Premiere of feature film City of Tigers on February 24 @4:40 PM at LOOK Cinemas (657 West 57th Street) as part of New York City’s 12th Annual Winter Film Awards International Film Festival. Tickets now on sale!

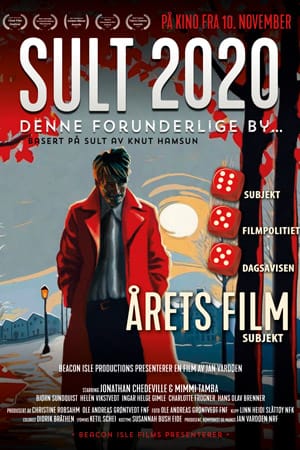

Jan Vardøen, the director and writer of the film City of Tigers (SULT2020), which is set in Oslo during the pandemic, says of his main character, “he wants to be an artist and feel the pain of being an artist.” Based on a novel that Norwegians are very familiar with, Hunger by Knut Hamsun, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1920, Vardøen’s City of Tigers has won awards and received accolades in his home country of Norway.

Vardøen, an independent filmmaker, has also directed the films Heart of Lightness, House of Norway, Høst: Autumn Fall, and a documentary on the life of composer Phillip Glass. House of Lightness and Høst: Autumn Fall are currently available on Netflix. Trained as a boat builder in his youth, Vardøen is also a restauranteur and author, and says of the unnamed main character in City of Tigers that “it’s well nigh impossible to starve” in the Norway of today and in the 1890s setting of Hamsun’s novel. However, in both the book and Vardøen’s film, it seems that the main character is attempting to starve, for art’s sake, and maybe not so much as a result of his financial challenges. The main theme of City of Tigers, Vardøen asserts, has to do with “who we see ourselves as,” and the filmmaker believes that adapting Hunger, which was made into a very well-regarded film in the 1960s, was also timely because of the strange circumstances people found themselves in during the pandemic.

“The sun shone warmly by now, it was ten o’clock and the traffic at Youngstorget Square was in full swing. Where was I to go? I pat my pocket to feel my manuscript; come eleven I would try to see the editor. I stand awhile by the balustrade observing the activity below me; meanwhile my clothes had started steaming. Hunger again announced itself, gnawing and tugging at my chest and giving me small, sharp twinges of pain. Did I have a single friend I could turn to?” The narrator and main character of Hunger, Hamsun’s masterful psychological novel, often called the first novel, says these words. City of Tigers, Vardøen’s film, is faithful to the text in that occurrences that take place in the Oslo of the 1890s – mostly in the summer and fall in the book – also happen in the film, just in a bleak 21st-century winter setting, and to a visual artist, not a writer.

“The sun shone warmly by now, it was ten o’clock and the traffic at Youngstorget Square was in full swing. Where was I to go? I pat my pocket to feel my manuscript; come eleven I would try to see the editor. I stand awhile by the balustrade observing the activity below me; meanwhile my clothes had started steaming. Hunger again announced itself, gnawing and tugging at my chest and giving me small, sharp twinges of pain. Did I have a single friend I could turn to?” The narrator and main character of Hunger, Hamsun’s masterful psychological novel, often called the first novel, says these words. City of Tigers, Vardøen’s film, is faithful to the text in that occurrences that take place in the Oslo of the 1890s – mostly in the summer and fall in the book – also happen in the film, just in a bleak 21st-century winter setting, and to a visual artist, not a writer.

“I think in both the 1890s version and this version, he has put this problem on himself,” Vardøen explains. The main character has his pride and though friends may notice he seems to be struggling – his appearance is unkempt and his clothes are shabby – they mostly don’t seem to want to offend the down-on-his-luck young man by offering him money or support. At times, however, the main character does accept help, but mainly he tries to keep up appearances. The tension of how much responsibility we have for others versus leaving them to fend for themselves, if, and when, we notice people may have fallen on hard times, is a constant focus in both the novel and the film.

“I think in both the 1890s version and this version, he has put this problem on himself,” Vardøen explains. The main character has his pride and though friends may notice he seems to be struggling – his appearance is unkempt and his clothes are shabby – they mostly don’t seem to want to offend the down-on-his-luck young man by offering him money or support. At times, however, the main character does accept help, but mainly he tries to keep up appearances. The tension of how much responsibility we have for others versus leaving them to fend for themselves, if, and when, we notice people may have fallen on hard times, is a constant focus in both the novel and the film.

“He really has normal human characteristics … he wants to show his best side,” Vardøen says of the main character. In City of Tigers, the artist follows a young woman whose name is never revealed – he just calls her “Ylajali” and she is a sort of muse to him, as is a similar character in the book. The scenes in both the film and the novel where Ylajali is featured are quite striking since the young woman eventually receives his interest warmly, but later comes to find something not-quite-right about this potential suitor. The unnamed artist also seems to enjoy lying to others and, at times, developing preposterous stories, perhaps to make himself feel better about his own circumstances. There is some joy and happiness in both the film and the book, though, and Vardøen, also a musician, composed the song, “King of the World” to accompany one particularly upbeat scene in the film.

“He really has normal human characteristics … he wants to show his best side,” Vardøen says of the main character. In City of Tigers, the artist follows a young woman whose name is never revealed – he just calls her “Ylajali” and she is a sort of muse to him, as is a similar character in the book. The scenes in both the film and the novel where Ylajali is featured are quite striking since the young woman eventually receives his interest warmly, but later comes to find something not-quite-right about this potential suitor. The unnamed artist also seems to enjoy lying to others and, at times, developing preposterous stories, perhaps to make himself feel better about his own circumstances. There is some joy and happiness in both the film and the book, though, and Vardøen, also a musician, composed the song, “King of the World” to accompany one particularly upbeat scene in the film.

Hamsun’s novel most likely will not be familiar to American viewers of the film and this will make seeing City of Tigers a different experience for these viewers than for Norwegians. Regardless of whether a viewer has read Hamsun’s book before, or has never heard of the book, he or she will be prompted to think about issues such as perception, fitting into society, privacy, and how we can and should support others. The film follows a stubborn, and perhaps gifted, individual who seems to associate lack, austerity, and pain with the true creative process. It is up to those who see the film or read the novel to discern whether or not this main character might be right, or whether a person could not become a brilliant writer or painter by accepting help from the state, or from friends, and allowing himself or herself to be decently housed, fed, and sufficiently clothed, in order to make art that matters.

Cristina Slattery

Cristina Slattery has written for publications such as The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Newsweek Japan, Forbes Travel Guide, Harvardwood Highlights, Roads & Kingdoms, The Winter Film Festival, FoodandWine.com, Words Without Borders, AFAR.com, Travel+Leisure.com, several airline magazines and other national and international magazines and websites.

About Winter Film Awards

New York City’s 12th Annual Winter Film Awards International Film Festival runs February 21-25 2024 in New York City and includes 82 outstanding films, a diverse mixture of animated films, documentaries, comedies, romances, dramas, horror films, music videos and web series of all lengths. Our five-day event is jam-packed with screenings and Q&A sessions at NYC’s LOOK Cinemas, six Education sessions/workshops and a variety of filmmaker networking events all coming to a glittering close on February 25 with our red-carpet gala Awards Ceremony.

Winter Film Awards is dedicated to showcasing the amazing diversity of voices in indie film and our 2024 lineup is 58% made by women and half by or about people of color. Filmmakers come from 23 countries and 41% of our films were made in the New York City area. 13 films were made by students and 26 are works from first-time filmmakers.

Winter Film Awards programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council and are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature. Promotional support provided by the NYC Mayor’s Office of Media & Entertainment.

Visit https://winterfilmawards.com/wfa2024/ for more information.