WFA 2023 Home Schedule Explore the Film Guide Education Parties News+Reviews

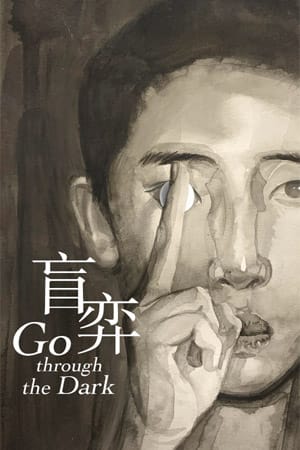

Guanglin Xu is a player of the board game ‘Go’. Demonstrating impressive skill at the age of 11, he also happens to be blind. Quietly, documentarian Yunhong Pu captures his story with intimacy and care.

By Abby Cole

See the feature film Go Through The Dark on February 18 @2:15PM at Cinema Village (22 East 12th Street) as part of New York City’s 11th Annual Winter Film Awards International Film Festival. Tickets now on sale!

In the opening scene of Go Through the Dark, two children sit across from each other, manning opposing sides of a game board. Next to them is another game board, bookended by two more children. In fact, many game boards and pairs of children are scattered throughout the room, elbow-to-elbow and eye-to-eye. It’s a tournament to determine player ranking in the game Go, and the feverish energy is palpable, the clacking of game pieces racketing off the walls.

Guanglin, eleven years old, sits across from his competitor, a young girl who watches him play his next move with apprehension. She glances at the two girls at the neighboring board, who are also watching Guanglin. Leaning forward to peer into his face, one girl mouths to the others, wide-eyed, “He’s blind.” She’s promptly shushed, but the girls continue to stare at Guanglin in what might be awe, confusion, or both, more interested in Guanglin’s playing than their own game.

“What a pity! How difficult is it without sight?” They continue to gesture to each other, frantically but silently. Guanglin never responds or indicates that he’s even heard them at all. They seem to be embarrassed to speak in Guanglin’s presence, as if his blindness makes it inappropriate to speak to or around him. He focuses intently on his own playing, carefully brushing over the board with the tips of his fingers and strategically placing pieces. Eventually, he wins the game.

Guanglin Xu is a masterful player of the ancient and notoriously complex board game Go. An exceptional player in his own right, demonstrating impressive skill at the young age of eleven, he also happens to be blind. Born in Anshan, China, Guanglin lost his vision due to childhood malnutrition, and his father explains that he can only see extreme changes in lighting — otherwise, the world is invisible. Where his disability might make the game Go seemingly impossible to play with its visual strategy, Guanglin flourishes, memorizing each piece as it is placed and holding an image of the board in his head throughout the game. He is quiet, careful, and serious, a small boy, and yet he often finds himself the center of attention, playing among a huddled group of fascinated onlookers.

Guanglin Xu is a masterful player of the ancient and notoriously complex board game Go. An exceptional player in his own right, demonstrating impressive skill at the young age of eleven, he also happens to be blind. Born in Anshan, China, Guanglin lost his vision due to childhood malnutrition, and his father explains that he can only see extreme changes in lighting — otherwise, the world is invisible. Where his disability might make the game Go seemingly impossible to play with its visual strategy, Guanglin flourishes, memorizing each piece as it is placed and holding an image of the board in his head throughout the game. He is quiet, careful, and serious, a small boy, and yet he often finds himself the center of attention, playing among a huddled group of fascinated onlookers.

His disability in addition to his impressive skill level at such a young age has led to his notable rise to fame within the Chinese Go community, catching the attention not only of amateur and professional Go players and a variety of media outlets, but also of documentary filmmaker Yunhong Pu.

Born in Harbin, China, roughly a seven-hour drive northeast of Guanglin’s hometown, Pu graduated with an MFA in Social Documentary Film from the School of Visual Arts in New York City. Go Through the Dark is her thesis project, as well as her first feature-length documentary. After witnessing the shame a friend’s father experiences because of his own blindness, even missing his daughter’s wedding to avoid embarrassing her, Pu began to notice disability in places where she hadn’t before. “I found there is a huge number of people with disability,” she recalls to me over email. “I feel so bad once I thought about they do not walk under the sunshine, they cannot chase their dreams as everyone else did. And because of my friend’s story, I realized that disability is not far away from everyone.”

Knowing she wanted to explore more about the disabled experience, she began searching for ways to bring more stories into the open. That’s when she discovered Guanglin. As an audience, our first impression of Guanglin is how he’s viewed through others’ eyes and how others interact with him. This theme becomes a thread woven throughout the entire documentary. While each person featured in the film is in some way concerned with Guanglin’s success in Go, Guanglin himself speaks very little, hovering just on the edge of conversations, listening in silence, whether a group of children rambunctiously play Plants vs. Zombies or his Go teacher dissects his strategic failures in front of a class.

He’s pointedly excluded, approaching other children with casual remarks and receiving silence as a response, as if he weren’t there at all. He stands in doorways and laughs, a fruitless attempt to integrate into a social group. His father notes that “he likes to stand behind them and listen to them talk.”

He’s pointedly excluded, approaching other children with casual remarks and receiving silence as a response, as if he weren’t there at all. He stands in doorways and laughs, a fruitless attempt to integrate into a social group. His father notes that “he likes to stand behind them and listen to them talk.”

At the center of the story, Guanglin nevertheless lingers just outside the various relationships in the documentary, listening to debates on what decisions can and should be made about his Go training or his disability. Not once do we hear a vocalization of his thoughts — however, brought intimately close to him through Pu’s lens, we get critical insight into the way that overhearing these conversations affects him. Invisibly, with the delicate expertise of a skilled documentarian, Pu captures quiet moments when Guanglin is upset, when he’s overwhelmed, when he’s happy and at ease. He never draws attention to himself. As viewers, it seems we’re the only ones who notice.

Pu’s relationship to Guanglin and his father were important during filming — it was essential that they felt safe around Pu so that she could be present in sensitive situations. One of the most important requisites for capturing such careful moments is trust. “During our communication, I showed them my thoughts and my attitude,” she explains. “That’s why they are willing to show their real thoughts and behaviors in front of my camera.”

Outside of a trusting relationship with her subjects, Pu also credits readiness as an important practical factor in documenting emotional scenes. She recalls one instance in which she momentarily left the shoot to buy herself a bottle of water. In the five minutes she was absent, she missed a shot that would have been valuable to the project. “You should always be in the right place to shoot while not attracting people’s attention,” she says. “No matter what and when, I try my best to keep my camera and myself ready.” Of course, shooting a project of this size as a single-member crew makes it even more difficult to be present for every important moment. After all, one person cannot be everywhere all at once. In the future, Pu says, she will try to avoid working on her own and will instead consider the value of teamwork that she now recognizes because of this project.

Thanks to Pu’s emphasis on trust and communication, it becomes clear that she has gained a unique insight into Guanglin’s experiences as a disabled person, and more broadly, as an eleven year old boy in China. In perhaps the most shocking revelation of the film, we find out that Guanglin’s blindness is likely curable. He remains blind merely because of his father’s hesitancy to treat him. It’s not that there are financial roadblocks — Ms. Wang, Guanglin’s first Go coach, offers to fund the entire surgery, plus room and board. Instead, Guanglin’s father refuses, citing to others that he is afraid curing Guanglin’s blindness might render him irrelevant in the Go community. It’s hard to watch Guanglin sit shrunken beside his father, who emphasizes that a cure would cause him to lose what makes him special. Besides, he insists, the anesthesia will affect his brain, and on top of all of that, Guanglin is scared of the surgery. Guanglin remains unresponsive at his side.

Behind the camera, Pu found herself dealing with these surprising truths in realtime. “When I first found out that Guanglin’s father was not going to treat his eyes for the present, like many audiences, I was shocked and confused,” she says. Nevertheless, having built a trusting relationship with Guanglin, one that is “like friendship,” Pu emphasizes the importance of capturing an honest story while resisting personal bias, choosing to respect her subject’s experiences and to represent them honestly. “I’ve learned that it’s hard to understand the reasons and perspectives of their decisions when I’m not in their shoes. Once this is understood, controlling my emotions is a matter of course.”

Behind the camera, Pu found herself dealing with these surprising truths in realtime. “When I first found out that Guanglin’s father was not going to treat his eyes for the present, like many audiences, I was shocked and confused,” she says. Nevertheless, having built a trusting relationship with Guanglin, one that is “like friendship,” Pu emphasizes the importance of capturing an honest story while resisting personal bias, choosing to respect her subject’s experiences and to represent them honestly. “I’ve learned that it’s hard to understand the reasons and perspectives of their decisions when I’m not in their shoes. Once this is understood, controlling my emotions is a matter of course.”

Guanglin’s father, Mr. Xu, remains at the center of conversations about Guanglin’s well-being. He alone cares for his son, serving as Guanglin’s sole form of guidance throughout his life, his mother having abandoned the family when he was only five years old. As Ms. Wang observes, “ only eats what his father puts on his plate.” He explains that, though Guanglin never claimed to miss his mother, he wears his blue jacket constantly, the only thing she ever gave to her son. He is told that he’s an admirable father for not abandoning his handicapped child. When they’re separated, Guanglin experiences nausea and loss of appetite. His diagnosis? A fear of abandonment.

Go Through the Dark is certainly a film about disability and ableism, about how Guanglin is repeatedly excluded from a society he longs to fit into. However, the specific themes of dependency appear again and again — the film doesn’t just address Guanglin’s dependency on his father, but also Mr. Xu’s dependency on his son. “It’s not his son relying on him, but the other way around,” a fellow Go student aptly summarizes.

Led to believe that Ms. Wang, who has provided Guanglin with free tuition and board at her Go school, is stealing money from him, Mr. Xu decides to return to their hometown and find another way for Guanglin to receive Go instruction. His anxieties about the family’s finances understandably weigh heavily on him as well as on Guanglin. Unfortunately, as a father, he is revealed to be verbally, sometimes physically, abusive, vocalizing his arguably understandable concerns about money and about supporting himself and his son. “I quit my job to be here and help as much as I can,” he explains as he eats a bowl of noodles. In the doorway behind him, Guanglin stands motionless, his arms behind his back as he listens. “But he has to be independent someday,” Mr. Xu continues. “His future will be up to him. If he can’t make it, he’ll live on handouts.”

Following this conversation, Pu, from behind the camera, asks Guanglin privately what he’s worried about. He explains, “Not enough money.” “If you go back, your dad can go to work and make money,” Pu gently reassures him. “But I need to take Go classes.” He fidgets, tears welling up in his eyes. “What about my tuition?” Quietly, he begins to cry.

Guanglin is no stranger to overhearing how important he is to his family’s financial wellbeing. In the following scene, Mr. Xu and a friend discuss the potential of Guanglin making enough money to support himself through Go, Guanglin pacing at the edges of the conversation. Minutes later, he stands aimlessly inside an adjacent room. “Why are you standing here?” Mr. Xu asks sharply. Guanglin remains quiet. “I’m asking you! What do you want?” his father shouts, and Guanglin still doesn’t respond, mouthing wordlessly an explanation that doesn’t emerge. His father shoves his head roughly with his hand, and Guanglin almost loses his footing but catches himself. “I’m asking you! Answer me!” He kicks him, and with a grunt Guanglin falls out of frame. “You know how annoying you are? Why don’t you answer? What the hell do you want?” A hand on his shoulder, his friend attempts to calm him down. “Just fucking say it!”

Guanglin is no stranger to overhearing how important he is to his family’s financial wellbeing. In the following scene, Mr. Xu and a friend discuss the potential of Guanglin making enough money to support himself through Go, Guanglin pacing at the edges of the conversation. Minutes later, he stands aimlessly inside an adjacent room. “Why are you standing here?” Mr. Xu asks sharply. Guanglin remains quiet. “I’m asking you! What do you want?” his father shouts, and Guanglin still doesn’t respond, mouthing wordlessly an explanation that doesn’t emerge. His father shoves his head roughly with his hand, and Guanglin almost loses his footing but catches himself. “I’m asking you! Answer me!” He kicks him, and with a grunt Guanglin falls out of frame. “You know how annoying you are? Why don’t you answer? What the hell do you want?” A hand on his shoulder, his friend attempts to calm him down. “Just fucking say it!”

Speaking afterwards to Pu, he explains that Guanglin’s skills in Go had finally given him hope that his son would have a future, despite his disability. “But sometimes, the greater the hope, the greater the disappointment.” The film ultimately hovers around one unspoken question that seems to go unconsidered by those closest to Guanglin, or perhaps one just dismissed as unimportant: what does Guanglin want? One of the few insights we get into Guanglin’s own opinion about treating his blindness, for example, is a brief, wide grin as he’s told that once his vision is restored, he will be able to travel, to see the colors of the world. The idea clearly delights him, and yet aside from this emotional expression, he never indicates a further thought on the subject.

We aren’t even sure if Guanglin enjoys Go at all. Certainly he appears disillusioned with the game toward the end of the film, laying his head on his arm during games, falling asleep, accenting his plays with sighs and slouching in his chair. With the aim to combat what he perceives as laziness, Mr. Xu attempts to encourage him: “You should rely on yourself, not others. Success comes from your own efforts. Since you love Go, just always try your best.” Guanglin doesn’t reply.

The documentary tells us that Guanglin is constantly deemed ineligible for many Go schools or competitions due to his need to have his father present for support. Today, Guanglin continues to face issues obtaining disability accommodations. Pu says they’ve been keeping in touch, and that his Go skills have been improving rapidly. However, “he’s been having some difficulties lately,” she notes. He signed up for the official national Go tournament — if you succeed in this tournament, you become a professional player and not just an amateur, something that could provide financial security for Guanglin and his father. However, due to a rule by the Go Association that disallows players to bring their own boards and game pieces, citing the potential to cheat, Guanglin was disqualified, only able to play with his own special board that allows him to feel the patterns of his pieces. But, as Pu says, “he and his father did not give up, and they are still trying to find a solution to this problem.”

Guanglin is certainly no stranger to such hardships. In the film’s ending, Guanglin even receives the “Award of Diligence” from his Go school for his relentless dedication to the game, and achieves amateur Level 5. Hand-in-hand, Guanglin and his father stroll into the distance. “Keep going?” his father asks him. “Yeah, keep going,” he responds.

Abby Cole

Abby Cole is a freelance writer and copyeditor from Dallas, TX. She has a Bachelor of Arts degree in both English and Film & Media Arts from Southern Methodist University. She is also an independent music producer and artist and spends her spare time reading prolifically, teaching herself niche skills like 3D modeling and oil painting, and somehow analyzing everything through the lens of gender and sexuality.

About Winter Film Awards

New York City’s 11th Annual Winter Film Awards International Film Festival runs February 16-25 2023. Check out a jam-packed lineup of 73 fantastic films in all genres from 21 countries, including shorts, features, Animation, Drama, Comedy, Thriller, Horror, Documentary and Music Video. Hollywood might ignore women and people of color, but Winter Film Awards celebrates everyone!

Winter Film Awards is an all-volunteer, minority and women-owned registered 501(c)3 non-profit organization founded in 2011 in New York City by a group of filmmakers and enthusiasts. Our mission is to promote diversity, bridge the opportunity divide and provide a platform for under-represented artists and a variety of genres, viewpoints and approaches. We believe that only by seeing others’ stories can we understand each other and only via an open door can the underrepresented artist enter the room.

Winter Film Awards programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council and are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature. Promotional support provided by the NYC Mayor’s Office of Media & Entertainment.

For more information about the Festival, please visit winterfilmawards.com