The shadow of the Cold War still loomed over my head as I prepared for my Skype call with actor-producer Evgeny Tarlo. I kept saying to myself, “Yes, soon I’m gonna have my meeting with the Russians.” The novelty never escaped my post-modern media soaked head that has grown up with an impression of Eastern European cinema revolving solely around high brow realism of Tarkovsky, maybe some constructivist style Soviet montage; there’s a limited canon in the Western zeitgeist. However my conversation with Tarlo regarding his new film Inner Fire has had me taken to task.

By Michael Piantini for Winter Film Awards

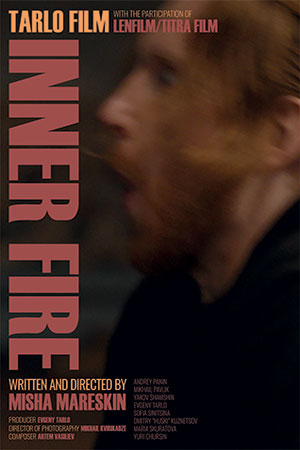

See the World Premiere of feature film “Inner Fire” on Wednesday Feb 26, 2020 @ 7:45 PM at Cinema Village (22 East 12th Street) as part of New York City’s 9th Annual Winter Film Awards International Film Festival.

Tarlo, at some point a lawyer, a politician as well as musician, found himself producing and starring in director Misha Mareskin’s film with a clear vision in mind. Perhaps with the intent to assist viewers like myself in seeing the velvet curtains draped around what he’d call the truth about humanity, and the broader character that is the Russian people.

Michael: Thank you for taking the time to speak with me. I first wanted to ask you about the style and the aesthetic choices in the film. How did you and the director come together to make those decisions?

Tarlo: It was fairly accidental. I didn’t actually mean to produce or play this role. I was contacted by a friend of mine who said that I look like the character. The character was supposed to be a villain and that’s how I connected to the movie.

Tarlo: It was fairly accidental. I didn’t actually mean to produce or play this role. I was contacted by a friend of mine who said that I look like the character. The character was supposed to be a villain and that’s how I connected to the movie.

M: As an actor, the character you play is the father of Gaga who isn’t in the present story of the film. How do you build a relationship that we never see?

Tarlo: So actually Gaga himself is in the movie, I was speaking with him on the phone, so he’s actually present in the movie. And when he does all these bad things like drug dealing, I as the father thought, “How do I feel about this and what should I do?” My kid, my son is doing all this stuff, this was my idea when I was talking on the phone. The problem I am saying with my character’s son was something that I tried to change in a different way rather than what people did in the Soviet-era movies. You see in the Soviet institution, the father, if he found things wrong and weren’t well, he’d have to teach that to his children. In my case, I changed my way of approach. I tried to help anytime.; not accusing him of doing something wrong, I understood he was doing something wrong, he was a bad guy. But since he was my son, my mission was just to help him any way at anytime. This approach was how I tried to solve this problem.

M: That’s an interesting approach to parenting.

Tarlo: Yes! In the beginning of the movie I’m asked, “Do you know your son is a killer? He uses drugs, he is violent!” And my character responds, “Yes I know these things but he’s my son.”

M: “My son is my son regardless of what he does, he is mine.” Do you believe there is any commentary invoked regarding Yakov Shamshin’s character and the things he says to Andrey Panin’s character?

Tarlo: Actually you know the thing is: they are telling each other the truth. At first they are well-established people the correspondent [Andrey Panin] has a doctoral degree, an established arts professor. The next guy [Yakov Shamshin] is an assistant to a high ranking official in Parliament. The third guy [Mikhail Pavlik] is a former professional dancer. And lastly, my character is a retiree. All of them are respected and established people, but at the same time they have their own bad stories. I’ll now cite a Gothe play: “Every person, whether be noble or disrespected, has a mystery in their story. If this mystery is revealed, they will be hated by everyone.” Once all of these characters’ secrets were revealed they became bad people, though at first they look like good people.

Tarlo: Actually you know the thing is: they are telling each other the truth. At first they are well-established people the correspondent [Andrey Panin] has a doctoral degree, an established arts professor. The next guy [Yakov Shamshin] is an assistant to a high ranking official in Parliament. The third guy [Mikhail Pavlik] is a former professional dancer. And lastly, my character is a retiree. All of them are respected and established people, but at the same time they have their own bad stories. I’ll now cite a Gothe play: “Every person, whether be noble or disrespected, has a mystery in their story. If this mystery is revealed, they will be hated by everyone.” Once all of these characters’ secrets were revealed they became bad people, though at first they look like good people.

M: I see. Every person regardless of their outward appearance has some internal garbage inside them.

Tarlo: Generally speaking they have garbage, but in truth it’s even worse than this because they have horrible secrets. Once revealed they are accusing each other of who has done the more horrible action in the past.

M: Tell me about production. Did you have any specific requirements for a scene? Were there any difficult scenes to shoot?

Tarlo: Shooting was done within one place. During one scene, there was an accident that happened to me. I was beaten by some bad guys, some hooligans, ya know. They broke my ribs and left some bruises on my face. And it was hard to run while we were shooting. If you look closely in the film, you can see a bruise under my eye but we covered it with makeup.

M: Oh wow!

M: Oh wow!

Tarlo: Sofia Sinitsina, who played the character of the secretary, had 27 attempts to shoot the film. But for the other challenges of the production: the fireworks, the coloring, and lighting. Because the film should be seen in very good digital quality because the director wanted to make some references to some artists. Therefore it is very critical to see color and lighting, it was very important.

M: Everything is particularly stylized in a certain way so I understand what you’re saying about seeing the film on a bigger screen to make it all worthwhile.

Tarlo: As well the music and the sound works together for the meaning of the film.

M: When audiences finish the film, is there anything you hope they walk away with?

Tarlo: The movie hasn’t gone public yet, we had a closed private screen with just close friends of the director. About 150 people were at that screening. Basically, there were some prominent critics at the screening, people with a high intelligence, they really appreciated the film with great feedback. People see this movie once and want to watch it two or three more times because of how the film develops they wanted to see it again. So hopefully people will feel the same at the film festival in New York and when it goes public.

M: I understand that. I’ve seen it twice now and the second time I picked up on foreshadowing elements. Knowing the characters brings out a lot for the movie. Do you think the film will translate well outside of Russia?

M: I understand that. I’ve seen it twice now and the second time I picked up on foreshadowing elements. Knowing the characters brings out a lot for the movie. Do you think the film will translate well outside of Russia?

Tarlo: The movie will have subtitles in French and English, and if distributors get interested we can then do dubbing in other languages. But the film has a global appeal, not just for Russia, it’s outside of politics. It is about the human soul, it is about human source of inner sins, and how it reveals itself. Because you know there is a lot of Dostoevsky character in the movie. A lot of inner ideas and psychology like Dostoevsky novels. Layer by layer in his soul [Andrey Panin] reveals itself and makes it for the better. This is common to any place, it’s about anyone.

M: My last question about cinema at large, specifically about predominantly-English speaking nations. Do you think there is a changing attitude towards films with subtitles?

Tarlo: You see, watching movies with subtitles is okay because the first thing that comes are the visual effects, what they see rather than what they read. As people watch them extensively, the sounds and visual effects they will understand the whole idea and subtitles will become additional information. So it won’t change the impact of the movie, especially if they watch the film two or three more times.

Also one more thing. I think the Western watchers will see Russian characters from the complete other side. They will change completely their character of the Russian people. Because the characters in the movie are children of Perestroika. If you remember, in the 90s after Perestroika some criminals were in the country and these children were raised among these criminals. Late 1999 into the new decade, they felt the impact of these criminal situations and this is how they tried to survive. The movie shows them from this side, previously not shown to those outside of Russia.

M: Breaking the stereotypes associated with Russian characters — for instance, your character is a gangster wearing the tracksuit.

Tarlo: We don’t want to specifically show we are different from other people; we show who we are. We show we have good things and bad things. Everyone, regardless if they are Russian or from any other country, has a good and bad side, including those who watch the movie. We’re showing the truth of life.

M: Thank you, this has been an enlightening new perspective on the film. Good luck to you in New York!

Michael Piantini

Born in the Dominican Republic, Michael Piantini migrated to the US when he was about 2 years old. His sense of self fostered in high school when the medium of film was introduced by a summer college course. Now he is a screen studies student at Feirstein Graduate School of Cinema. Using his developed cerebellum he writes films, essays, and thought pieces all to figure out how to express emotional honesty while living in the 21st century!

About Winter Film Awards

New York City’s 9th Annual Winter Film Awards International Film Festival runs February 20-29 2020. Check out a jam-packed lineup of 79 fantastic films in all genres from 27 countries, including shorts, features, Animation, Drama, Comedy, Thriller, Horror, Documentary and Music Video. Hollywood might ignore women and people of color, but Winter Film Awards celebrates everyone!

Winter Film Awards is an all volunteer, minority- and women-owned registered 501(c)3 non-profit organization founded in 2011 in New York City by a group of filmmakers and enthusiasts. The program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council and the NY State Council on the Arts.